Aircraft Carrier Meatball - To provide a new level of assistance to the pilot, but allow him to continue hands-on flying, Kindley and his team have developed the Maritime Augmented Guidance with Integrated Controls for Carrier Approach and Recovery of Precision Enabling Technologies.

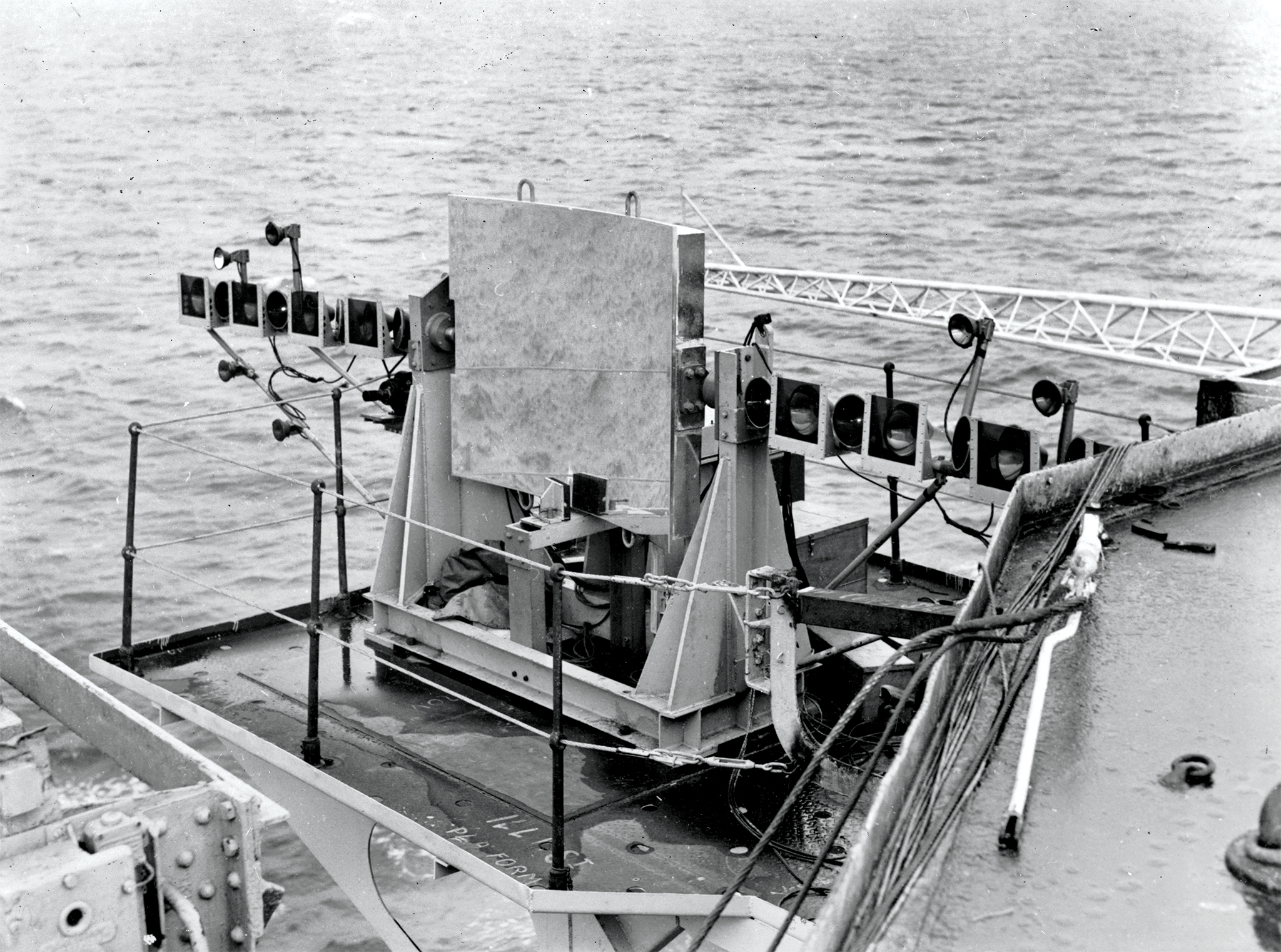

Even by military standards, that's a mouthful. They call it Magic Carpet. When you think of carrier landings, a few essentials probably come to mind—hook, wire, and the "Meatball," known by its full name as the Improved Fresnel Lens Optical Landing System, or IFLOS.

Aircraft Carrier Meatball

While the Meatball is known to be a critical component for fixed-wing pilots landing on catapult and arresting gear-equipped (CATOBAR) carriers, it's less known that America's 'big deck' amphibious assault ships (LHDs and LHAs) are also equipped with the

Uss George Washington By The Numbers

system. Thanks to one Harrier pilot who goes by the handle @overdesigned on Twitter, we get to see the system in action right from the cockpit of his AV-8B Harrier. The result, Kindley believes, will be less time and money spent on introducing pilots to carrier landings and keeping them current.

He continues to gather more data, but he is convinced that over time safety will improve and, thanks to more predictable landings, maintenance on both the aircraft and the ship can be reduced. Magic Carpet surely seems to hold great promise.

"Monotonous," though? That's a tall order. Meanwhile, to us landlubbers, the short visit to the carrier was a reminder of the sacrifices our service members make day and night around the world. Day in and day out, personnel on the carrier, home at times to as many as 5,000 sailors and air crew members, work in dangerous, uncomfortable, and confined positions to ensure our freedoms at home.

While enjoying your Independence Day celebrations this weekend, stop for a moment to say thanks to a service member for what he or she has done to keep us safe and free. Do you "call the ball"—where the pilot acknowledges visual contact with the Meatball at 3/4 mile from the ship and their fuel state—like fixed-wing aircraft operating aboard supercarriers do?

Are the radio communications similar in general? The next time you're having trouble staying aligned with the runway on a windy day, consider the challenge of a naval aviator approaching an aircraft carrier at 130 knots with the runway moving to the right and forward at 20 knots.

Land short, and you die. Land long, and you die of embarrassment later in the debrief. The U.S. Navy spends about $1 billion a year getting pilots qualified for carrier operations and keeping them current. Kindley and a team of Navy pilots, technicians, engineers, and software wizards want to reduce that cost and improve carrier landing efficiency and safety.

Their solution is a flight control system software upgrade to the Super Hornets and the EA–18 Growlers that is designed to make carrier landings "monotonously repeatable." (navy.mil) ATLANTIC OCEAN (May 13, 2013) Electrician's Mate 3rd Class Martin Torres, from Long Beach, Calif., calibrates an Improvised Fresnel Lens Optical Landing System (IFLOLS) aboard the aircraft carrier USS George H.W.

Bush (CVN 77). George H.W. Bush is conducting training operations in the Atlantic Ocean. (U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 3rd Class Kevin J. Steinberg/Released) The jet blast panel emerges from the deck, another signal that the launch is imminent.

The quadruple tail surfaces and the towering dome atop the fuselage shudder as power is advanced. The pilot wiggles the control surfaces for a final check and then gives the ready signal. As one former naval aviator puts it, the pilot also pushes the "I Believe" button, attempting to assure himself that his colleagues outside and the equipment around him are truly ready for the wild ride ahead.

A spotter makes one final check of the area and with the push of a button the steam-powered catapult hurtles the big airplane off the slowly rising deck and into the night. We onlookers gasp as the Hawkeye grabs air and struggles away.

The deck hands, confident in their work and their equipment, looked hard and quickly began preparations for the next one. The burble, of course, messes with a stabilized approach, requiring last-minute adjustments. All this occurs under the constant watch of the landing signal officer, aka Paddles, himself an experienced Hornet pilot standing near the aft end of the ship.

If at any time he senses the arriving aircraft is not stable in pitch, roll, or airspeed, he will wave it off. He's also the one who scores every landing—and, as a result, he is the most reviled member of the pilot crew.

Often, the scores are posted for others to see. The grades range from the best being an "OK" then to "Fair"; any poor landing receives a “No Grade.” Pilots who score less than an "OK" usually feel the LSO is like the proverbial umpire who needs glasses.

For the crews, our arrival on the USS George Washington aircraft carrier was routine, but for those of us who were experiencing a landing trap for the first time, it was anything but. The creaky old C-2 Greyhound twin turboprop carried us from Norfolk, Virginia, out to the carrier, a couple of hundred miles offshore in the Atlantic Ocean.

Sitting backwards in the windowless cabin, we listened intently through dual levels of hearing protection as the engine sounds changed and the gear thunked into position. As if flying down a drinking straw, the pilot expertly flew a three-degree glide path to the moving runway, catching the coveted number three wire as we were slammed into the seat backs.

The carriers have an automated landing system (ALS) that allows for hands-off touchdowns. But it requires the ship's precision radar, which can be finicky and unreliable. Additionally, the system requires an electronic link between the ship and the aircraft.

"If you transmit, you can be found," says Kindley. In addition to the requirement that numerous systems on two moving vessels work perfectly, the final approach for an ALS is much longer than for a normal landing.

That eats up "seascape," which can be critical in parts of the world where bodies of water are narrow or there are busy shipping lanes; it also delays aircraft recoveries, which can be critical during inclement weather or challenging military or political situations.

Kindley plans to introduce Magic Carpet to the fleet in 2017 for more feedback while he and the team develop system redundancies that will allow Magic Carpet to be a fully functioning and fully trusted system for the Super Hornets and Growlers in 2019. The next generation of fighters

, the F–35 Lightning, will come with Magic Carpet technology already in place. One major difference between the Meatball on America's nuclear-powered supercarriers and those on big deck amphibious assault ships is where it is mounted.

Instead of being installed on the port side amidships at deck height, it is mounted on the island superstructure, on the ship's starboard side, high above the deck. As you can see in @overdesigned's video below, he flies the meatball straight in, over the fantail of the ship, before entering into a solid hover and eventually touching down vertically amidships:

With coaching from outside the sim by James "Buddy" Denham, a senior engineer for the Naval Air Systems Command, I managed to snag the 3 wire without Magic Carpet on the first try. Indeed, the F/A–18 is easy to fly—during the day when everything's working and no one is shooting at you.

My biggest challenge was understanding the symbology on the head-up display and looking for the "meatball," the visual glidepath guidance system. Next time, I switched the augmentation on as I rolled out of the constant-bank turn onto final.

With Magic Carpet assisting, I aligned my glidepath with the meatball and let pressure off the stick. The airplane started down at 3.5 degrees. I just needed to apply slight left and right corrections. Once, a little low, I pulled back and "elevated" back up to the meatball and let go again.

Abeam the touchdown point, an F/A–18 Super Hornet pilot rolls into a 28-degree constant-bank turn until intercepting the approach path. The goal is to be on the back side of the power curve. Level off, but don't balloon up.

Power back and pitch over to set up an angle of attack of about 8 degrees to follow a glidepath of about 3.5 degrees. The "meatball" on the carrier's deck, a Fresnel lens system, provides a visual indication of the glidepath.

However, the whole thing is moving forward and to the right in an attempt both to provide a headwind to slow the approach speed and reduce the runway required, and to keep the angled deck pointed into the wind.

The Grumman E-2C Hawkeye emerges from the dark shadow of the aircraft carrier's towering island, its wings folded. A moonless night, the twin turboprop maneuvers across the ramp, lit only by the dim lights embedded in the deck.

Everywhere, crew members scurry about, staying clear of the eight-blade propellers and the 81-foot wings as they unfold. The crew's red, green, blue, yellow, brown, and purple shirts signify their role in launching the early warning aircraft.

According to Kindley, a pilot will make on average 200 to 300 minor corrections during those 18 seconds in the groove. Do it right, and the Hornet hits the deck at 800 feet per minute, the tailhook snagging the coveted Number 3. To be sure, the pilot goes to full power at touchdown.

If he's missed all the wires, he'll fly away to try again, or maybe have to hit the tanker, which is always overhead whenever air operations are going on. Meanwhile, an H-60 helicopter with swimmers on board is hovering off the starboard side, ready to swoop in and pluck a pilot from the sea should an ejection or crash occur.

AOPA Pilot was invited to the George Washington to witness the final day of a five-day sea trial of Magic Carpet's latest software version. The crews flew 598 approaches with only one miss during the trial, and this was with test pilots purposefully aggravating the system and also flying with and without head-up display (HUD) guidance, with and without autothrottles, single-engine, and at times

with compromised flight controls. Generally speaking yes, in that it gives us visual glideslope from a mile or so out towards the ship. We transition to a different set of lights once we're in close though, whereas CVN pilots fly the ball all the way to touchdown.

The Hawkeye crew makes a left traffic pattern and soon plunks down on the angled deck for a touch and go, one more step towards proficiency. Meanwhile, just off to the right, an SH-60 Seahawk helicopter hovers under the stars, ready to swoop in for the rescue should it be necessary.

So there you have it. There are some real similarities and differences between how Harriers land on amphibs at night to how fixed-wing aircraft land on supercarriers at night—the latter of which you can read all about here.

While the Meatball may still be the go-to aid in both cases, new concepts of operation and capabilities are making recovering aboard ships at night a bit easier. Kindley and company are quick to point out this is not an automated landing system.

The pilot is hands on, flying the entire time. But Magic Carpet frees up mental processing power, allowing the pilot to increase situational awareness and make better decisions. "There are two kinds of military pilots," says Kindley.

"Those who see themselves operating a weapons system and there are those who are there to fly." In addition to seeing the Meatball in action, the straight-in approach isn't something we see much of when it comes to Harrier ops aboard amphibious assault ships.

So, with all this in mind, we reached out to the guy at the controls to get more info on this approach, the Harrier's use of the IFLOS, and more. Things are difficult with a rolling ship, particularly at night on NVDs, without a well-defined horizon.

If you attempt to match the ship's roll with your aircraft you start to slide laterally, so you have to watch the tramline [centerline of the takeoff and landing area] for left/right alignment while also ignoring the roll of the ship itself.

Without a horizon that is challenging. The burble is a pocket of disturbed air behind the carrier's island, the tall superstructure that houses the bridge, "pri-fly" (primary flight control), and the infamous "Vulture's Row" where visitors and other pilots go to critique every landing as

it happens. The Hornet enters the burble in the final seconds before touchdown, hoping to catch the Number 3 wire and make the perfect trap. Any of the four wires will do in a pinch, but you'll hear about it later if you don't hit the 3.

The software upgrade decouples the Super Hornet and Growler's fly-by-wire flight controls, allowing the computers to individually control each axis without disturbing the others. With conventional controls, when you roll into a turn, you need to add a little nose-up elevator, plus add some rudder to correct the yaw.

Each minor change requires multiple control inputs. IFLOLS receives ship's pitch and roll information from either the ship's gyros or SPN-46. IFLOLS receives ship's heave information from either an IFLOLS generated ship's heave signal or SPN-46.

The IFLOLS signal is generated using the IFLOLS unit 5 accelerometer. The IFLOLS can use either ship's pitch and roll gyro source with either heave source. When aircraft are landing using ACLS, any mode, IFLOLS should use the same stabilization inputs as SPN-46.

Typically SPN-46, SPN-41, and IFLOLS will all use the SPN-46 gyro for pitch, roll, and heave information when aircraft are landing using ACLS. Some former naval aviators I've spoken with wince a little at the idea of "augmentation."

Still, no doubt, future aviators will appreciate the assistance that frees up more brain power for other tasks. And, Kindley believes taxpayers will appreciate the lower training and maintenance costs he believes will result when Magic Carpet is fully implemented in 2019.—TBH

Later, Denham pulled out all the stops, failing the head-up display and the autothrottles, and transitioning us to night flight. Predictably, I had several bolters, including a "cut pass"—down the starboard side, nevertheless—the worst thing that can happen to a carrier pilot short of ending up in the drink.

Everyone on the ship and especially those turkeys on Vulture's Row know you just screwed up major league. However, after 20 or so approaches, I made more traps than not, Magic Carpet working hard to reduce pilot workload.

For approaches where we use the ball, yes the ball call is the same. There are a couple of extra calls related to the vertical landing that occurred after the ball call. For a normal daytime good weather recovery, we just call abeam, no ball call.

And then similar to how a CVN LSO [Landing Signal Officer] provides guidance, the V/STOL [Vertical/Short Take-Off and Landing] LSO does the same, but again with some specialized terminology related to the hover and vertical landing.

The arrival kicked off our 30-hour stay on the massive carrier, which was doing sea trials of a new flight control system designed to make it easier for pilots to nail the three wires every time.

Fewer bolters means less fuel, safer operations, and faster recovery of the squadron. The approaches are all done on the back side of the power curve. Because of engine lag, a pilot's ability to respond to a dynamic flight environment is challenged.

In a word, the airplane is sluggish. Magic Carpet, though, takes over all the flight controls and the four flight control computers, forcing any combination of flight controls necessary to respond instantly to deliver what the pilot needs.

"It's like a bird landing on a wire, the whole trailing edge of the wing is moving and adjusting," explains Denham. "[Magic Carpet] opens the last chapter of the last 100 years, to give the pilot the speed and flight path that he wants."

Slow down or speed up, Magic Carpet does what it must to maintain that same glidepath to the ship. From 450 feet above the water, you'll have about 18 seconds "in the groove," the final approach portion of the arrival.

"I put the white line on the deck between my legs," says Dominick in the briefing room about the USS George Washington as it steams north and south off the Virginia coast. Our arrival to witness the U.S.

Navy's Magic Carpet augmented flight control system trials aboard the USS George Washington was abrupt, the aging Grumman C2 Greyhound slamming onto the 1,092-foot flight deck, catching the 3 wires. Our chance a couple of weeks later to experience it ourselves, though, was less dramatic, my Bonanza touching down on Patuxent River Naval Air Station's 11,800-foot Runway 24 (see "Waypoints: Logic: So Overrated," October 2016 AOPA Pilot).

Capt. David Kindley, the Navy's F/A–18 and EA–18G program manager, was on hand to show how easy it is to land an F/A–18 Super Hornet on a carrier. "The F-18 is the easiest airplane to fly, easier than a Cessna," promised the longtime general aviation pilot as we headed for the simulator.

aircraft carrier landing light system, retired aircraft carriers on display, improved carrier optical landing system, how many ships in a carrier group, landing on a carrier, aircraft carrier landing grades, fresnel lens on aircraft carriers, mothballed aircraft carriers in philadelphia